After much detective work, scientists at Kent-based NIAB EMR have formally identified a potentially damaging new weevil that has been making itself at home in several pear orchards in the UK. Rachel Anderson reports.

The case of the pear blossom weevil (Anthonomus spilotus) is perhaps a timely reminder to the UK’s horticulture industry of the need to be vigilant when dealing imported plant material. Scientists at Kent-based fruit research centre NIAB EMR were first alerted to this new weevil a couple of years ago by Kent fruit grower Clive Baxter, who warns us that the insect caused an 80 per cent “drop in crop” in one of his older orchards.

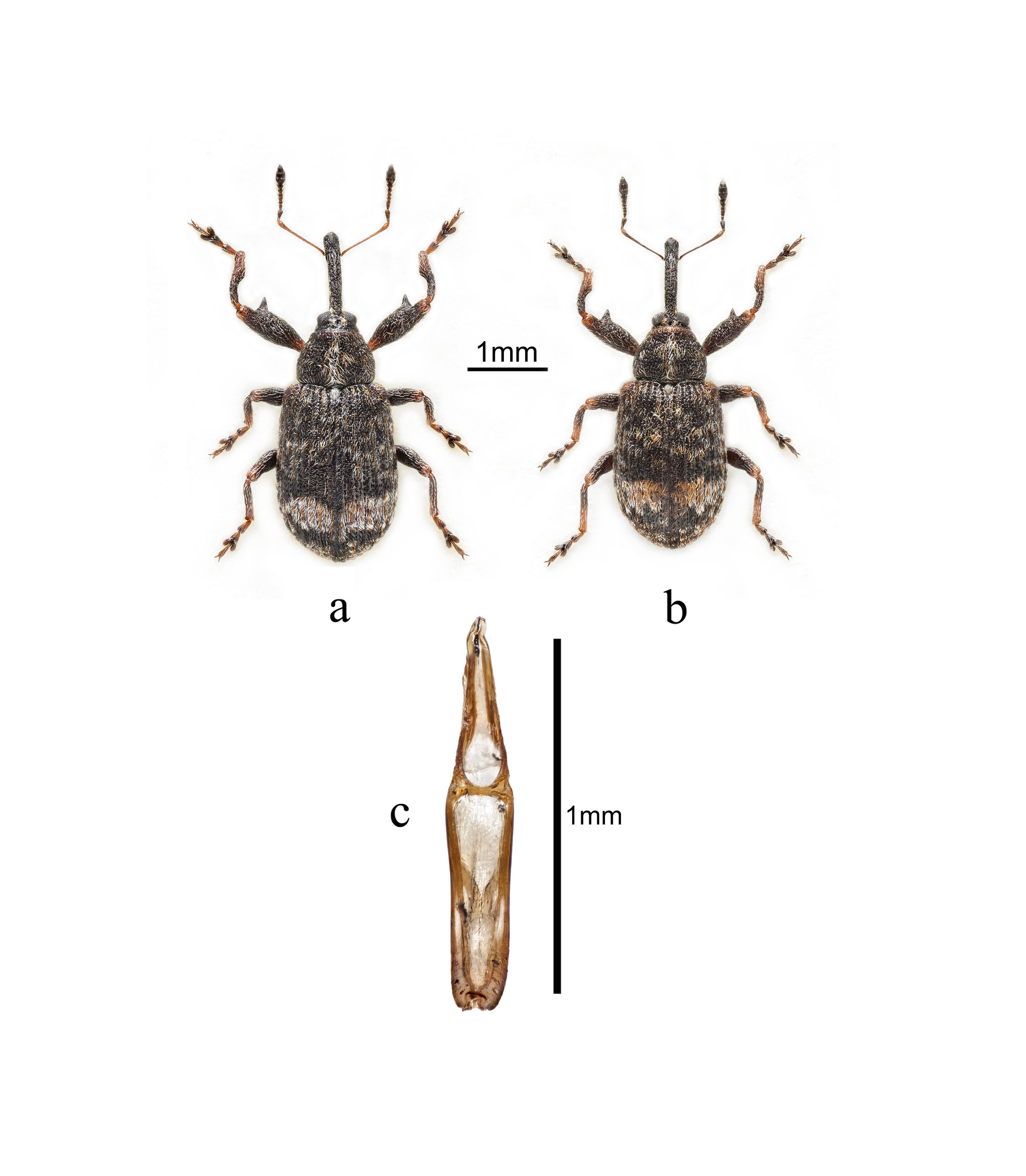

Initially, the bug’s unwelcome appearance left the team at NIAB EMR a trifle confused. It bears a striking resemblance to the pear bud weevil (Anthonomus piri) and the apple blossom weevil (Anthonomus pomorum), but its lifecycle is different. NIAB EMR’s Madeleine Cannon says: “We found that A. piri lays its eggs in the autumn – and we were getting damage in spring, which suggested either that potentially pear bud weevil adults were overwintering and the adults were laying in the buds in spring or it was a different species.”

Fortunately, whilst the NIAB EMR specialists were investigating the matter, they unearthed an old French reference book which helped them to successfully identify the pest. Madeleine adds: “We then sent some specimens to the [UK’s] Natural History Museum and it was finally confirmed that it was pear blossom weevil (Anthonomus spilotus).”

Experts surmise that this weevil might have tiptoed in from mainland Europe in plant material that was destined for our garden centres. For instance, it could have been hiding in the compost of potted plants (as the weevil pupates in the soil) or the weevil’s eggs or larvae could have been lurking inside the plant buds.

Potentially, because of the way that the weevil may have been introduced, it could be located sporadically across the UK – although, so far, it’s only been spotted in pear orchards in the south east.

Experts have also deduced that this surreptitious insect has been able to thrive in the orchard underworld because pear growers – in their efforts to promote beneficial insects – have been making fewer insecticide applications.

The beginning of March is when the adult weevil starts to devour both leaf and flower buds before the female lays her eggs in her own feeding holes. Pear growers are therefore advised to put on their Sherlock Holmes-style deerstalker hats and start inspecting their orchards for feeding holes in flower and leaf buds. They should examine their orchards weekly (until June) by tap sampling tree branches before making a careful decision over the need to use control measures and their choice of plant protection products (PPPs). Preliminary trials in the field and the lab have shown that several PPPs effectively control adults in the spring. One such PPP is Calypso (thiacloprid), which also returned Clive’s cropping to normal. Trials this year are further testing these products.

Madeleine and Clive were speaking at the Agrovista fruit technical day, held at Brands Hatch, Kent, earlier this year (2018).

Picture Credit - Harry Taylor (2017) and the Natural History Museum

On closer inspection, pear blossom weevils are “a bit more fancy” than their fellow weevils-in-crime. “They tend to have a bit of a pattern,” explains Madeleine, “you get some weevil species which are jet black or a completely uniform colour.” The pear blossom weevil also has an ash- or white-coloured transverse band on its back, which is perpendicular to its wing cases. The ginger hairs on its body are another characteristic to watch out for when identifying the pest – which causes damage to the new growth and vigour of trees.