Eric Carle’s famous children’s book, The Very Hungry Caterpillar, sees a little caterpillar daily eat his own bodyweight in snacks before metamorphosing into a striking butterfly. The sheer volume of food that my growing eight-year-old son consumes throughout the day reminds me of this very story. On Monday, for example, my son ate three bowls of cereal, two ice creams, one chocolate brownie, some fish and chips, a fruit salad, and a generous helping of his mum’s spaghetti Bolognese. But he was still hungry.

Whilst we are on the subject of hungry little grubs, let’s talk about Bemisia tabaci (tobacco whitefly). For, if growers fail to take the necessary precautions, these crop-munching, non-indigenous whitefly could decimate their young poinsettia crops faster than a flock of seagulls attacks a Cornish pasty.

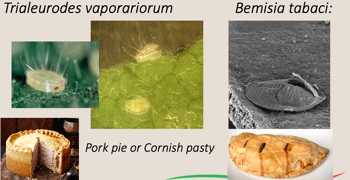

Funnily enough, Bemisia’s empty pupil case resembles exactly that. Its likeness to a Cornish pasty has been cleverly observed by Fargro’s IPM Specialist Neil Helyer, who’s also highlighted that the end-of-the-pupil stage of glasshouse whitefly (Trialeurodes vaporariorum) resembles another traditional British delicacy – the pork pie. But before we all start dreaming of a ploughman’s lunch, let’s take note of Neil’s top tips for preventing the spread of tobacco whitefly.

Early monitoring

Firstly, growers should maintain good weed control, particularly around structures and under benches. And, as the pest can arrive on cuttings imported from warmer climates, growers must be prepared and get their yellow roller or sticky traps out early.

Neil asserts: “Whitefly monitoring is absolutely essential before, during and potentially after the life of that particular crop. If any whitefly are found, get them identified [liaising with your local plant health inspector] at the earliest opportunity.”

“Monitor the whole crop and determine any varietal preferences and ‘hot spots.’ Place copious yellow sticky traps in and around ‘hot spots’ – this will kill migrating adults and limit their spread.”

Neil adds: “If you do find any whitefly, ring them round with a biro so you don’t count them again and again. And it’s essential to record what you are finding and where you are finding it.”

With their whitish-coloured wings, tobacco, glasshouse, and honeysuckle whitefly (the latter of which also pops up in poinsettia crops) species each look confusingly similar – so growers should also be mindful of that.

Sorry to make you peckish again, but aubergine plants – sat amongst the poinsettias about half a metre taller than the crop – make great “banker plants” that, explains Neil, act as a very good green flag for any migrating whitefly or other pests.

He says: “This approach has been very successful. Aubergine will attract adult whitefly. They are also attractive to aphids, spider mites and thrips.”

In the early stages of production, Neil recommends applying biopesticides in preference to conventional chemical pesticides – mainly because there may already be chemical pesticide residues on the young, imported plants. “Also, if we go with pesticides early and we end up with a problem later, we’ve already used up the limited number of pesticide applications that we have.”*

Whilst growers are advised to hang up sachets of Amblyseius cucumeris in the aubergine plants, they need not place predatory mites (Amblyseius montdorensis and Amblyseius swirskii) into the poinsettia crop until after pinching. “There’s little point in bringing those predatory mites on before pinching because you are going to remove [parts of] the plants. So, put them on after pinching and you should get a much better control of the early stages of your whitefly,” explains Neil.

Predatory wasps, such as Eretmocerus eremicus and Encarsia formosa, can then be introduced at a rate of one wasp per plant for at least the next five to six weeks. E. eremicus, reveals Neil, is particularly good at tackling tobacco and honeysuckle whitefly.

Finally (and before I go shopping to restock my fridge), if growers suspect the presence of, or find, Bemisia tabaci, they should inform, and work with, their agronomist and their local Animal and Plant Health Agency (APHA) Plant Health and Seeds Inspector.

Neil Helyer was speaking at AHDB’s Managing Bemisia in Poinsettia Crops webinar that took place in June 2020.

*Crop protection products (registered biopesticides and pesticides) that currently have on-label approval in the UK for use against Bemisia include Applaud, Batavia (EAMU), Flipper, Gazelle, Mainman, Mycotal and Naturalis L.